Do our pupils need support for bolster their writing development?

In my last blog, I posed the question about whether there was a hidden problem with the damage wrought by the pandemic on pupils who have joined secondary school. The evidence of a dip in national date at both Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 1 is obvious.

The solutions to such national and school level challenges are less obvious. Writing has often been described as the ‘neglected R’ compared to reading and ‘rithmetic (maths). Schools can invest in programmes and interventions, but consistent high quality teaching is going to be essential for the greatest number of pupils.

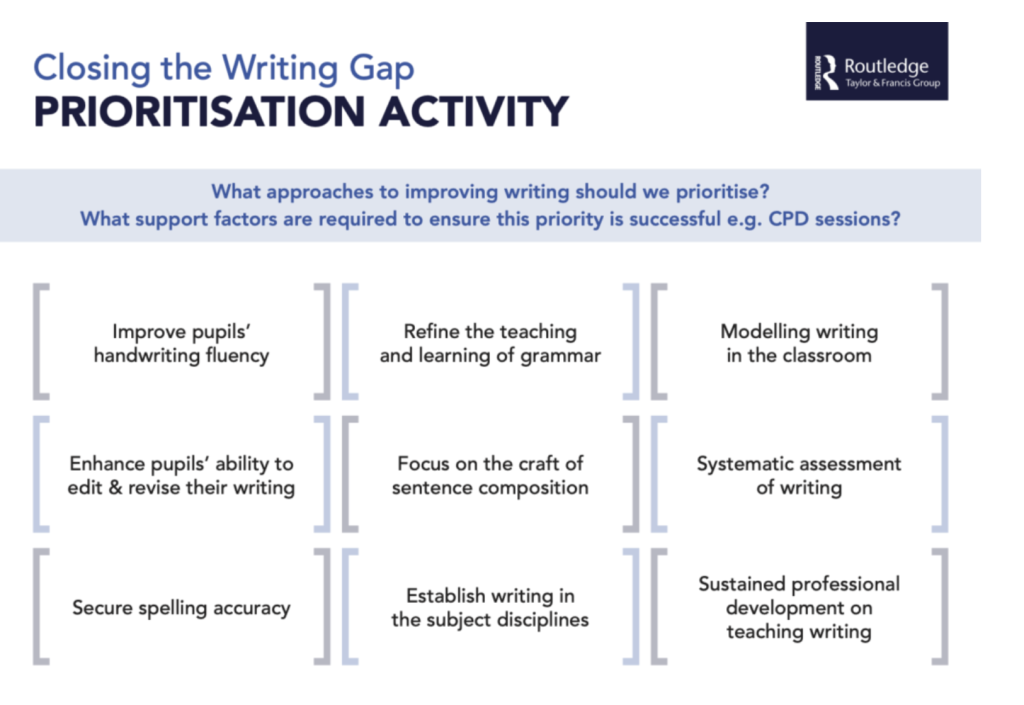

In developing ‘Closing the Writing Gap’, surveying research evidence and my engagement with schools indicated that the following 9 priorities were most commonly being tackled in schools:

- Improving pupils’ handwriting fluency. Too often, handwriting is written off – particularly for older pupils. And yet, automatic, fluent handwriting is essential to ensure that pupils can focus their mental effort on more higher order processes. Using handy diagnostics, such as the ‘Handwriting Legibility Scale’ can help identify struggling pupils. Programmes can be deployed and teachers can be upskilled to make this a manageable priority (the National Handwriting Association offers helpful resources to steer practice – HERE).

- Secure spelling accuracy. Spelling is often a focus in primary school, but goes onto be an afterthought in secondary school. The research on spelling instruction indicates that sustained explicit teaching is required. ‘Look cover write check’ and the year 5 spelling list are unlikely to be enough. We can focus on homophones, approaching morphology and targeted vocabulary instruction, for a richer solution. In secondary schools, there need to be a sustained focus on a small number of manageable strategies, wedded to vocabulary teaching, editing writing, and other practices.

- Focus on the craft of sentence composition. The chess game of writing has countless moves and so it can overwhelm our novice writers. Focusing on sentence level approaches is a meaningful and manageable way to support explicit instruction. There are four common approaches that are best bets: sentence combining, shrinking, expanding and signposting. These variations can be applied and used for younger pupils and to start subject specific approaches. For instance, The Writing Revolution sentence signposts ‘Because, But, So’ has proven popular for science. And yet, we need to see beyond one-off sentence tricks and see crafting sentences as a way to enhance how pupils think.

- Refine the teaching and learning of grammar. Grammar often inspires fear or indifference. Does spotting verb phrases improve writing. Well, the grammar, punctuation and spelling assessment in year 6 probably doesn’t lead to better writing, but we can apply grammar to writing successfully. To close the ‘grammar gap’ of teacher knowledge, we need to build everyone’s confidence and translate it into writing moves. ‘Grammar for writing’ can directly lead to writing improvement.

- Enhance pupils’ ability to edit & revise their writing. ‘Editing’ and ‘revising’ writing is particularly tricky for novice pupils. First, they need to know the difference. Editing is the secretarial correction of errors, but revision is making quality differences to meet the needs of the audience (even if that is the teacher). Lots of deliberate practice is needed with these practices, shrinking down the challenge e.g. can a checklist for editing make a difference, or can pupils be allocated in ‘editing teams’? In short, pupils need clear, consistent routines (in secondary school, this standard for writing also needs to be set across every subject in the curriculum).

- Establish writing in the subject disciplines. Does writing really matter in subjects like art and design? The answer is a resounding yes if pupils are to write to learn to write well across the curriculum. Of course, there is a requirement for ‘disciplinary literacy’ and teacher training. For instance, from note making, to help pupils develop balanced arguments in religious education will require lots of primary age practice, support to structure paragraphs, use sentence signposts, deploy evidence and more. This will not happen without explicit teaching. This will not happen unless teachers are supported to understand approaches for ‘disciplinary writing‘.

- Modelling writing in the classroom. Modelling to writing development is like exercise and diet to a healthy body. Shared writing can be nuanced and tricky, with teachers (especially new teachers) lacking in confidence in how to do it. Whether it is visualiser or whiteboard, a whole school approach to modelling writing can pay dividends. The value of worked examples is simply too powerful to miss.

- Systematic assessment of writing. The assessment of writing can get bogged down in imitating dodgy GCSE mark schemes, or dubious year 6 moderation messages. Instead, we might identify tight priorities, by focusing on the likes of sentence composition or spelling, or adapting a rubric like WAM, we can be more targeted in diagnosing issues and pinpointing priorities. Hard thinking about writing assessment may see a more varied approach that aping national assessment rubrics (such as exploring ‘comparative judgement‘ and other innovative approaches).

- Sustained professional development on teaching writing. Sustained high quality professional development is always needed, but with the complexity of writing development, it is simply a pre-requisite. We need to offer teachers training, time and tools to solve the issue (whilst school leaders can meet the necessary mechanisms for effective CPD).

Useful support resources:

Find the prioritisation poster and other ‘Closing the Writing Gap’ resources HERE.

Find ‘Closing the Writing Gap’ online: Amazon UK: HERE. & Routledge: HERE. (Use CWG20 for a 20% discount)

I am undertaking the popular Teachology ‘Closing the Writing Gap’ masterclasses in June in Manchester and Birmingham (and online) – see more HERE.