Are pupils new to secondary school this year prepared for the challenges of academic writing?

After a couple of terms of secondary school, it becomes clearer whether pupils are getting to grips with the academic demands. As they write narratives in English, essays in history, notes in science, or annotate in art, pupils are expected to quickly assimilate a host of subject specific writing moves.

In reality, most teachers of art, science, history, geography etc. are busy teaching the curriculum, with writing proving something of a means to an end. We may expect a good standard of accuracy – with some proof-reading here and there – but it would be commonplace to expect all year 7 pupils to ‘write to learn’ each day with little explicit support.

Writing aids thinking. If pupils cannot write fluently, automatically, clearly and cogently, then their thinking slows. As a result, the burden on working memory for difficult new learning gets higher; every subject proves harder. That is before you consider the implications for timed exams and similar.

Houston, we may have a problem.

Has the pandemic irrevocably damaged pupils’ writing development?

Lots of year 7 pupils are unlikely to have automated the key skills of academic writing. Their progress was clearly hampered by the global pandemic that crashed its way through the middle of their key stage 2 teaching.

The damaging impact of the pandemic is clear for the new year 7 cohort currently in secondary school if we look back to their national assessments last year. If we compare national writing outcomes from 2019 to last year, it shows that only 69% of pupils met the expected standard in writing, down from 78% in 2019. *1

Unlike reading, writing does not have a common battery of assessments that are used in secondary schools. In most schools, year 7 is a time to ascertain standardised reading scores, reading ages, cognitive ability assessments and more, but writing is routinely absent from the assessment regime when compared to assessing reading gaps.

As a result, there may be a writing problem in secondary schools that is largely going undiagnosed and unaddressed.

Are pupils writing more accurately than they were in year 6? Has their spelling improved? Are they using a wider repertoire of academic vocabulary necessary for the ‘disciplinary writing’ in science and similar? Are they using well-crafted sentence structures to express mature ideas? Have they developed upon their ability to craft well-structured arguments? Are paragraphs coherent and well organised?

I think of my own son, whose writing development still needs explicit support, but who is now having to navigate a huge curriculum across a range of teachers who are unlikely to be trained in the explicit teaching and support that is required.

The issue for secondary schools is that many of these issues are near-hidden from view. It can lead to a series of small losses that impact on learning in cumulative fashion. When writing notes based on an explanation in geography, pupils can be using up their precious working memory bandwidth and spelling corrections, composing clear sentences, and repeatedly reading back through their writing to ensure it makes sense.

There is no silver bullet solution here. There is no blog, ‘5 top tips’, or book, that solves all this in an easy share. A recognition by disruption wrought by the pandemic is ongoing and cumulative is necessary – but resource-poor middle leaders need ample support in response. We need better diagnostic assessment of writing to understand whether there is a hidden problem, or whether our pupils have defied expectations and key stage 2 assessments in record time.

First, we need to begin exploring and assessing the potential of a hidden writing problem holding back pupils in secondary school. It may be a diagnostic focus on handwriting, spelling, the building blocks of writing sentences, modelling, how to write better in specific subjects. Put simply, for pupils who are struggling to write, it will not be enough to plough on through the planned key stage 3 curriculum.

*1 Additionally, grammar, punctuation and spelling outcomes were also down from 78% to 72% in the same timespan which may reveal related issues[1]. However, it is unlikely that labelling grammar in sentences for the test is an accurate indicator, or support, for improving pupils’ own writing.

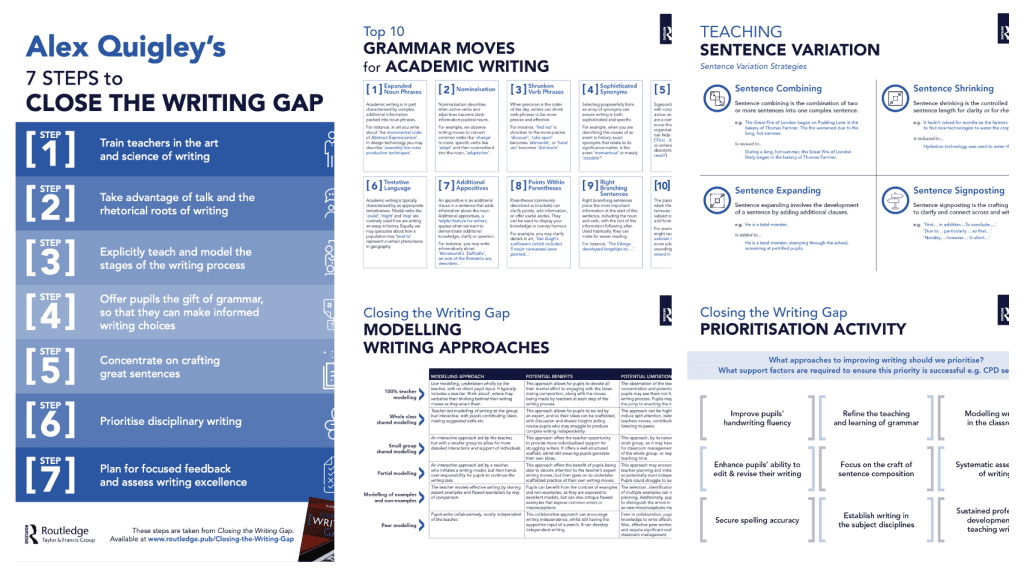

See my resources page for free ‘Closing the Writing Gap’ tools – HERE.

Source