We can take the brilliant complexity of sentences for granted. Each sentence written in the classroom is a distillation of a near-infinite number of complex moves.

For pupils, practising one sentence brilliantly may be worth a hundred sentences written in haste.

Too often, in the classroom, sentences are modelled, but pupils don’t have a strong concept of difference sentence level moves, their functions, and how to manipulate them. Instead of tackling lots of different genres and undertaking lots of error strewn ‘big writes’, we should be explicit in deliberately practising crafting great sentences.

When pupils are supported to over-learn sentence crafting, they can begin to understand how sentences are constructed differently in stories compared to scientific writing, from history essays to art evaluations. By honing the four key sentence variation strategies, pupils have the tools to master writing in any subject or genre.

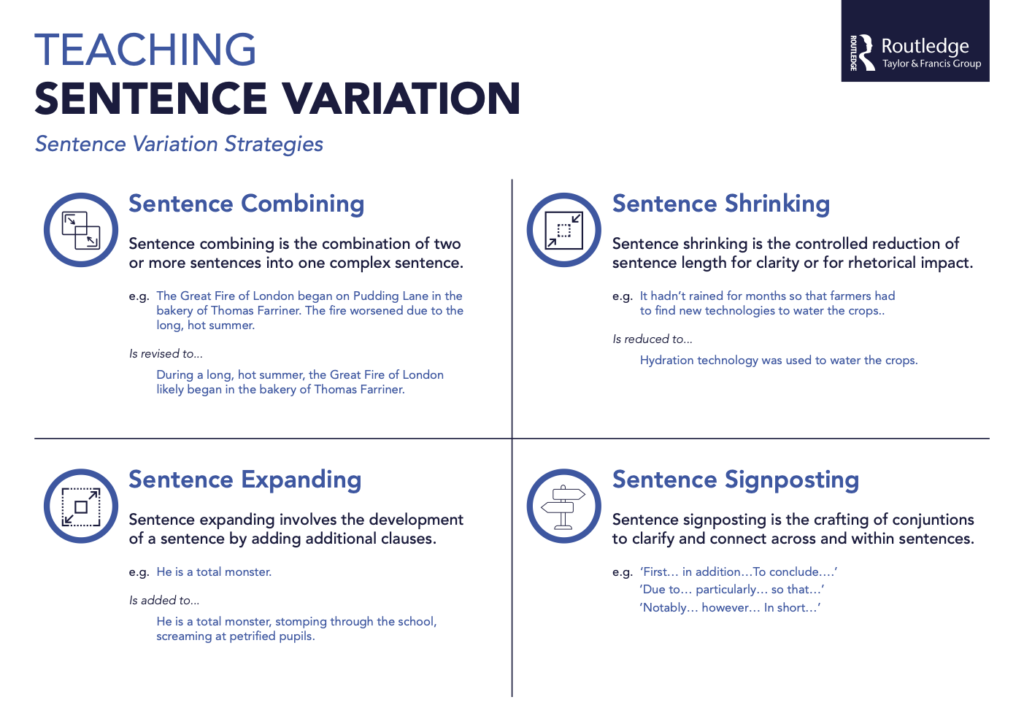

Sentence variation strategies

There are four key sentence variation strategies that pupils can explicitly practice. They can be closely related, but they are likely best practised in isolation, with scaffolds, under pupils are confident in that writing move.

1. Sentence combining

Sentence combining has been shown to be very helpful for struggling writers. At its simplest, it models the creation of more complex sentences. For instance, ‘The boy was hungry. He ate pizza’ becomes ‘The hungry boy ate pizza.’

For younger pupils, sentence combining begins their journey to writing great stories, as well as constructing more mature arguments. For secondary school pupils, sentence combining becomes a method to practise sophisticated academic writing.

For example, in geography, a bullet point list can be combined into a complex, single sentence:

- ‘The Earth’s crust is the lightest rock layer.

- It is thin compared to other layers.

- Around 5km to 70 km thick.’

The list becomes:

‘The Earth’s crust is the lightest, thinnest rock layer, at around 5km to 70km thick.’

In history, you can combine disembodied facts to convey more sophisticated and connected claims:

- ‘Wilberforce helped accelerate the end of slavery

- He gave inspirational speeches on slavery in parliament

- He helped create the ‘Proclamation Society’.’

The list becomes a richer academic sentence that transforms facts into effective historical claims:

‘Wilberforce helped accelerate the end of slavey with repeated inspirational speeches in parliament, whilst the Proclamation Society he helped to create, shared these moral messages more widely.’

[Read this excellent guide to sentence combining by AERO HERE]

2. Sentence shrinking

Great sentences are long and complicated, right? A crucial misconception held by pupils is that bigger is always better when it comes to sentences in the classroom.

Indeed, we can encourage pupils to trim their bloated ‘purple prose’ with a bit of sentence shrinking too. For instance, ‘The rugged, weather-beaten adolescent boy gazed with hunger and adoration at the sumptuous banquet’, becomes ‘The rugged teen gazed hungrily at the banquet.’ A sentence desperately aiming to impress becomes purposeful and clear.

Such compression of language is good for playing with writing styles for different purposes, but it is also great for modelling effective note-taking.

For instance, this definition of cracking is from the BBC Bitesize website:

“Cracking is a reaction in which larger hydrocarbon molecules are broken down into smaller, more useful hydrocarbon molecules, some of which are unsaturated: the original starting hydrocarbons are alkanes. the products of cracking include alkanes and alkenes, members of a different homologous series.”

You can successfully shrink it to the summary sentence:

‘Cracking: conversion of alkanes into smaller and more valuable hydrocarbons (such as alkanes and alkenes) through the breaking down of larger hydrocarbon molecules.’

At the extreme, you could summarise Hamlet as ‘a tragedy of revenge and existential angst’. Pupils need to understand when to shrink and when to expand a sentence.

[Read this brilliant article on writing short sentences HERE.]3. Sentence expanding

Sentence expanding may prove the most common sentence level move in the classroom. We may want more evidence in history, more description in a food science, more imagery in English.

Handled with care, lots of modelled sentence expanding can be the key to developing pupils thinking in academic language. For instance, in art, we may want to get pupils to show off their knowledge of a great painter. ‘Leonardo da Vinci was a great painter’ becomes ‘Leonardo da Vinci was a great painter who famously painted the enigmatic Mona Lisa.’ Showing knowledge may complement showing a little more style too.

We can scaffold expanding sentences for young pupils by starting with a simple sentence:

- He was a monster.

- [Adjective addition] He was a gentle / miniature / raging monster.

- [Add a clause for what he can see] He was a gentle monster, nervously peering out of his cave.

- [Add a clause for his next movement] He was a gentle monster, nervously peering out of his cave, before he went to hide under his blanket.

Equally, a simple sentence can be expanded with a focus on adding in details for ‘Who? What? When? Where? Why?’

We can model sentence expanding to explore evidence for a point in religious education:

- ‘Christians believe the afterlife includes…’

Or in business studies, it could focus on pupils activating their prior knowledge:

- ‘Three crucial benefits of business expansion include: …’

You can begin to expand sentences with specific grammar moves, such as adding an ‘appositive’ phrase (a short phrase that adds extra description to a noun) e.g.

‘Henry VIII, [insert appositive], removed the powerful presence of the Catholic Church.’

Depending on your interpretation, Henry can be a ‘notorious tyrant’, or ‘radical king’.

In science, sentence expanding can be used to challenge misconceptions e.g.

‘Some people believe deoxygenated blood is blue, although…’

‘Some people think evaporation and boiling are the same thing, however…’

Sentence expansion, with an increasing awareness of the grammatical moves at play, has an infinite amount of functions in the classroom, from making accurate definitions in geography, to crafting creative sentences for stories in English.

[Read this short ThoughtCo. article on sentence expanding with some handy activities HERE]

4. Sentence signposting

Sentence signposting is as old as ancient Greece. Aristotle, in his early texts on rhetoric and grammar, made clear the value of connecting and clarifying the relationship within and between sentences.

Too often, sentence signposting is reduced to listing FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so), or endlessly repeating a sentence structure formula that begins to stunt pupils making the own sentence level moves.

Teachers can organise and deploy targeted signpost clusters with specificity by phase and the subject matter of the writing (effectively forming more sentence expansions):

- Year 5 pupils balanced argument on school uniforms: You can introduce your argument with the cluster, ‘First…so that…as a result…’, whereas the classic counter- argument can be framed by the ‘In contrast…due to… however…’ cluster.

- Year 7 design technology new product brief: You can begin with the cluster, ‘First…furthermore…so that…’ to introduce your product, followed by a cluster to focus in on one specific element of the product development, such as ‘Due to…for this reason…notably…’

- Year 10 biology summary of diffusion of cells: You can begin with an introduction to diffusion of cells with the cause and effect cluster, ‘First…so that…consequently…’, followed by exemplification of diffusion in the lungs with, ‘For example…due to…as a result…’.

As pupils routinely build arguments and similar with signposts, simpler signposts can be replaced by more sophisticated expressions.

Carefully deployed – with exemplification, modelling, sentence stem supports, and more – these signposts can offer an understandable structure for our pupils to build successful sentences.

[Find the Talk for Writing’ connective/signpost phrase bank HERE]

Related Reading:

- Aspects of this blog are adapted from my chapter on ‘Crafting Great Sentences’ in my ‘Closing the Writing Gap’ book – see HERE and HERE (GAP30 gets 30% off).

- The US book, ‘The Writing Revolution’, is rightly popular with teachers. Read Tom Needham’s blog on its most famous strategy ‘Because, But, So’ – HERE.

- Christopher Youles has written an excellent new book entitled ‘Sentence Models for Creative Writing’ – HERE.

………………………………………………….

You can attend my Teachology masterclass on ‘Closing the Writing Gap‘ in Manchester (incl. online) and Birmingham this summer – see HERE.